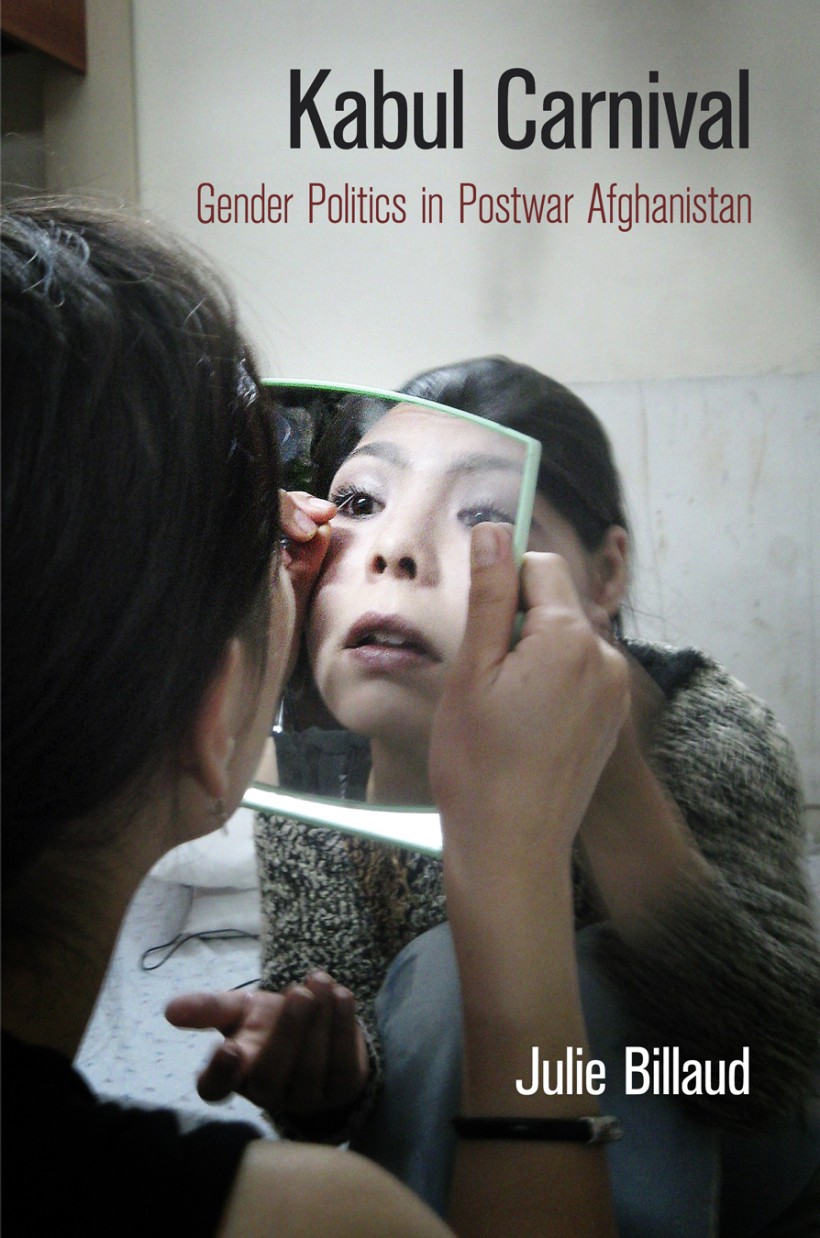

This post originally appeared on AllegraLaboratory.net, and features two Penn authors, Heath Cabot and Julie Billaud, discussing Billaud's book, Kabul Carnival: Gender Politics in Postwar Afghanistan. Cabot is the author of On the Doorstep of Europe: Asylum and Citizenship in Greece.

+ + +

Heath: Your book is in part an ethnography of how women (as both a category and a set of gendered performances, tactics, and ideologies) become a battleground, so to speak, for the making of contemporary Afghanistan. Did you set out to work on issues of gender? How did you decide to focus on Afghanistan?

Julie: Gender issues had been on my mind for a long time when I decided to embark on a PhD in a anthropology program. In fact, I discovered anthropology through a class on ‘Gender Discourses and Relations in Europe’ taught by Jane Cowan at the University of Sussex. I found the course so fascinating that I chose to write my MA thesis on a Paris-based group of women activists for peace in the Middle East called ‘Women in Black’. In this piece of work, like in my work on Afghanistan, I was interested in observing the various ways in which women become ‘visible’ in public, that is to say: how women become politically legitimate subjects with a voice of their own. Women in Black gathered once a week on a square in Paris’ city center, dressed in black, holding posters with slogans against the occupation of Palestine. The setting they had created to stage their protest was inspired from the Madres of the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, who organized weekly marches to denounce the disappearance of their sons during the Dirty War of the military dictatorship between 1976 and 1983. Like them, Women in Black remained silent, their presence on the square acting as a public reminder of the conflict and of their loss (symbolic or real) as mothers of Israeli and Palestinian children. Their performance was of course consciously gendered: it tapped into nationalist representations of women as ‘mourning mothers’ but also challenged such representations by bringing women in a space traditionally reserved to men: the square, the ultimate political arena.

Julie: Gender issues had been on my mind for a long time when I decided to embark on a PhD in a anthropology program. In fact, I discovered anthropology through a class on ‘Gender Discourses and Relations in Europe’ taught by Jane Cowan at the University of Sussex. I found the course so fascinating that I chose to write my MA thesis on a Paris-based group of women activists for peace in the Middle East called ‘Women in Black’. In this piece of work, like in my work on Afghanistan, I was interested in observing the various ways in which women become ‘visible’ in public, that is to say: how women become politically legitimate subjects with a voice of their own. Women in Black gathered once a week on a square in Paris’ city center, dressed in black, holding posters with slogans against the occupation of Palestine. The setting they had created to stage their protest was inspired from the Madres of the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, who organized weekly marches to denounce the disappearance of their sons during the Dirty War of the military dictatorship between 1976 and 1983. Like them, Women in Black remained silent, their presence on the square acting as a public reminder of the conflict and of their loss (symbolic or real) as mothers of Israeli and Palestinian children. Their performance was of course consciously gendered: it tapped into nationalist representations of women as ‘mourning mothers’ but also challenged such representations by bringing women in a space traditionally reserved to men: the square, the ultimate political arena.

Julie Billaud during her first fieldwork with ‘Les Femmes en Noir de Paris’, 2002. Credit: Jean-François Delamarre.

With my PhD, I redirected my focus on Afghanistan, a country where I spent a year as a humanitarian worker short after the intervention of the coalition forces in 2003-2004.

Because the intervention had been justified by the necessity to put an end to ‘gender apartheid’ – as some human rights defenders called it – I thought it would be useful to scrutinize what this externally imposed ‘liberation’ would concretely mean in practice.

The women I met during my first journey in Afghanistan had little in common with the ones depicted by the international press. Far from being the passive victims of religious fundamentalism, I found politically engaged and extremely resourceful women who had things to say about the future of their country. My book is a modest attempt at retrieving these voices and at providing a more accurate representation of the complex reality of Afghan women’s lives under foreign occupation.

Heath: You make wonderful use of Bakhtin’s notion of the “carnivalesque” from Rabelais and his World to set the stage for the series of performances that constitute reconstruction-period Afghanistan. Can you tell us more why this metaphor is so important for the book? What happens when the “carnival” becomes gendered?

Julie: The idea I am trying to articulate with the ‘carnival’ metaphor is that the current agenda for the ‘empowerment of women’ is part of a broader humanitarian theater that serves to promote an impression of normalization for Western audiences while hiding the continuity of violence and injustice at the local level. Indeed, the reconstruction of Afghanistan has been presented as a return to normality after long years of war and authoritarian rule. This discourse has fed the illusion of an absolute reversal from an old order characterised by brutality to a new one characterised by ‘democracy’, ‘the rule of law’ and ‘gender justice’. However, a closer look at the inconsistencies, paradoxes, and ambiguities that have accompanied the ‘reconstruction’, especially in the sensitive arena of gender, reveals that this rhetoric of reversals is anchored in a long history of foreign-led ‘modernization’ programs disconnected from the social reality of the people who are supposed to benefit from it.

Indeed, the ethnographic material I present in my book demonstrates that the international community’s concern with the visibility of women in public has ultimately created tensions and constrained women’s capacity to find a culturally legitimate voice. The recent lynching in Kabul of a young woman called Farkhunda falsely accused of burning the Koran has to be understood in this very tensed context marked by deep inequality and the emergence of lumpen youth in thrall of radical Islam and violence. While the ‘reconstruction’ has opened new possibilities for women and created new imaginaries pertaining to their role in society, the ideological framework (i.e liberal notions of equality and human rights etc.) on which it is grounded together with the strong military presence of foreign troops, have triggered moral panics around ‘identity’. Pressurized by their community to remain faithful to their ‘culture’, ‘religion’ and ‘tradition’ on the one hand, and encouraged to access the public and become ‘visible’ by global forces on the other hand, women stand on the frontline of a symbolic battle between competing notions of ‘honour’, ‘modernity’, ‘democracy’, and the role of Islam in society.

Left with little choice but to adapt and find alternative ways to preserve some degree of autonomy, women too have had to engage in carnivalesque performances. Here I am referring to the more positive aspect of Bakhtin’s notion of carnival, i.e its regenerative potential, its liberating power.

Heath: As a reader, I had some glimpses into your field experience, both in terms of issues of personal safety, emotional intensity, and the range of spaces and social worlds that you navigated. But you are refreshingly nonchalant about this – you don’t give us a picture of the ethnographer as hero/warrior, though you easily could. How did you manage doing ethnographic work in a space that is in conflict/post-conflict? What does doing fieldwork in such fraught socio-political spaces offer for the practice of ethnography more broadly?

Julie: Afghanistan was not totally unknown to me when I started my fieldwork, even though the situation had changed quite dramatically between my first journey in 2003-2004 and my second in 2007. If security conditions had worsened, I returned to a country where I had a few friends and contacts on which I could rely. I also learnt the language, which was a key element for building trust with the people I met. Finally, I secured a position in a company specialized in social marketing. I worked there for a few months until I made enough contacts in the circles I was interested in studying to continue fieldwork on my own.

Since 9/11, many places on the planet have become the target of Western military interventions. This interference is often justified by the need to ‘fight terrorism’, ‘implement the rule of law’ and ‘bring democracy’.

Like in earlier colonial enterprises, some (very problematic) ‘anthropological knowledge’ about the ‘culture of others’ is mobilized to develop the moral grammar legitimizing these occupations.

In the case of Afghanistan, ‘local’ culture is often described (in the international press as well as in NGOs and IOs’ reports) in fixed and essentialist terms, as traditional, conservative, responsible for all the ills of society. It seems to me that it is the role of anthropologists to fight such stereotypes and bring back politics and history at the center of our analysis.

Heath: The first half of your book is structured around the notion of “phantom” state building, regarding colonial/ post-colonial/ humanitarian approaches to constructing the Afghan state and nation. Can you tell us more about what you mean by “phantom” in this context?

Julie: The first part of the book focuses on the historical and political dimensions of the women’s question within the complex process of nation-building in Afghanistan. I provide a historical overview of the fashioning of the Afghan nation through the lenses of gender and I locate the current project of ‘nation-state building’ in the continuity of a series of ‘failed’ modernization attempts conducted in the early 30s, the 60s-70s and during the Russian occupation of Afghanistan.

What I am trying to demonstrate is that from the outset the Afghan state has remained a figment of the imagination, which in the reconstruction limbo mostly manifests itself through the use of violence, symbolic or real.

Indeed, if state infrastructures such as schools, hospitals, courts, police stations etc. have been rebuilt and partially staffed, the traditional Weberian functions of the state are shared with a myriad of other actors, such as NGOs, UN agencies, the World Bank, private companies, and local militias and narco-traffickers. Most state infrastructures remain dysfunctional for lack of trained personnel, financial resources and widespread corruption. For these reasons, the state cannot be analyzed in terms of ‘apparatus’ or ‘structures’ but is better described as a ghostly entity whose boundaries remain elusive, porous and mobile.

However, if the ‘state’ is difficult to grasp, it remains a powerful object of fantasies for both representatives of the international community and ordinary Afghans. Even though Afghans tend to be cynical in their relation to the state, the discourses that have accompanied the reconstruction regarding the state’s duties (especially concepts such as the ‘rule of law’ or ‘gender justice’) have increased Afghans’ expectations towards the state. This tension is a distinctive feature of the ‘postcolony’, which I am trying to unpack in the book, using various ethnographic examples collected in the Afghan judiciary and in the Ministry of Women’s Affairs.

Heath: You have numerous important interventions that you make in the book. But the two overarching arguments I take away pertain to how we conceive of culture and agency, as you intercede in longstanding debates in anthropology AND in development discourse around these ideas and practices. Would you be willing to tell readers a bit about how you have sought to reframe and rearticulate these highly charged terms?

Julie: Modernisation theory originally considered ‘culture’ as a barrier to development. Early modernizers shared the view that for a society to develop, social engineering should go hand in hand with technological innovation. Legal reform, especially in family matters, was therefore a central element of development programs carried out in the South in the 1950s up until the 1980s. It is interesting to note that if the ideological framework that guides the reconstruction is slightly different, it is still possible to draw parallels with modernization projects that took place under the previous regimes, notably the one of Zaher Shah and the communist regime that came later on. All of these ‘modernization’ attempts were marked by a strong emphasis on gender issues. In Afghanistan, like in Turkey under Ataturk or in Syria, Iran and Iraq during the same period, the construction of the modern state implied the reshaping of gender relations through state-led programs for the emancipation of women. To a great extent, the current focus on ‘women’ mirrors these earlier developments.

What one often hears in development circles and among the political elite is that the main barriers to the emancipation of women are to be found in ‘Afghan culture, customs and traditions’. I think these explanations are problematic because they take for granted the notion of ‘culture’ as if it could be easily pinpointed, as if ‘culture’ never changed or was never discussed.

It seems to me more accurate to consider ‘culture’ as a battleground or as a political field (in Bourdieu’s sense) where different actors, with different subject positions and agendas struggle to impose their own version of ‘culture’. Such a conception of ‘culture’ allows us to envision room for agency, especially for women who, in the current context, cannot express horizons of desires without being considered as ‘traitors sold to foreign forces’. For this reason, their ‘resistance’ to both Western interventions and to local politics needs to be articulated within a legitimate and audible cultural frame. In the book, I show examples of these dynamics in various contexts and settings in order to deconstruct the widespread idea that ‘agency’ necessitates clear ‘break ups’ with ‘culture’ or ‘tradition’, as mainstream Western feminists tend to believe.

Heath: The book includes numerous discussions of Afghanistan’s fraught relationship with highly westernized notions of “modernity,” both currently and historically, during various periods of “reform.” In the second half of the book, however, you show how Afghan women themselves practice and aspire to what Lisa Rofel might call “other modernities.” How does “the modern” function in contemporary Afghanistan? Do you see any of the alternate modernities that you portray gaining traction in wider public spheres (both in Afghanistan and globally)?

“Women at a demonstration in Kabul” (original caption). From The Revolution Continues, eds. Makhmud Baryalai, Abdullo Spantghar, and Vladimir Grib (Moscow: Planeta, 1984), p 58.

Julie: In Afghanistan like anywhere else for that matter, there is no consensus on what constitutes the ‘modern’. However, the collective memory has kept traces of the ‘modernization’ programs carried out by the various governments and their Western supporters from the 1920s onwards. To a great extent, the type of society the Taliban strove to establish was a direct reaction to such programs, from which a large part of the mainly rural population had been excluded. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the chaos that reigned after their departure was interpreted as a sign of the political elite’s corruption. Only a return to a strict version of Islam, they believed, could bring law and order back to the country. This meant, in practice, implementing policies diametrically opposed to the ones implemented by the previous regimes: When the communists had encouraged women to join the workforce, unveil and take part in politics, the Taliban locked them in their homes, forced them to veil entirely and to remain silent in public.

Because women’s subjectivity has been shaped by these historical developments, as well as by their experience of displacement and exile during the war, their interpretation of and aspirations to modernity is fundamentally complex and fragmented. Like in the case of China Rofel describes, Afghan women do not simply embrace Western cultural models. Their practices reveal that local forms of meaning are enmeshed in increasingly larger spheres of class, ideology, nation, and global capital which provide a fertile ground for ‘other modernities’ to emerge.

Some of my readers will perhaps find it surprising that I spend so much time discussing women’s beauty practices in Kabul but to me, the amount of time, money and thoughts women spend on bodily matters and the intense public controversies around the question of what to wear, are revealing of the continuing colonial anxieties around ‘modernity’ that the occupation contributes to perpetuate.

Heath: A more specific and personalized question: The question of ethnicity I found particularly fascinating, as in my own fieldwork in Greece I had contact with numerous Afghans from multiple ethnic backgrounds – but in particular, Hazara men and women who, like some of the women you discuss in your book, had been in exile in Iran. You suggest, however, that aspects of “culture” and “tradition” often linked to ethnicity are less important in distinguishing different groups of women than the experience of exile, which made Hazara women more willing and perhaps able to connect with other foreigners such as yourself (and perhaps ultimately in Europe). How does ethnicity figure (or not) in social hierarchies and divisions among women in Afghanistan?

Julie: I was sometimes criticized for not treating the ethnic issue with sufficient rigor in my work. This is perhaps because, as you rightly highlight, the experience of migration during the successive Afghan wars has deeply transformed Afghan’s subjective experience of ethnicity. Many Afghans have discovered their ‘Afghanness’ abroad and ironically, it is when returning ‘home’ that they had to face stigmatisation as ‘foreigners’. Hazaras, in particular, who were (and to a large extent still are) considered the ‘underdogs’ of society (a bit like the Dalits in India), had to endure this extra layer of discrimination when returning from long years of exile in Iran. In the girls’ dormitory where I boarded for 4 months, Hazara returnees were able to share rooms with girls from other ethnic groups, based on this similar experience of exclusion.

This is another evidence of the relative influence of ‘culture’ and ‘ethnicity’ in the reproduction of social hierarchies in Afghanistan.

+ + +

Julie Billaud is a Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. Kabul Carnival: Gender Politics in Postwar Afghanistan is available now.

Heath Cabot teaches anthropology at the College of the Atlantic in Maine. On the Doorstep of Europe: Asylum and Citizenship in Greece is available now.