Today’s post comes from Jon Repetti, a Visiting Fellow at the APS Press (with whom Penn Press has a recently launched partnership) and a PhD Candidate in English at Princeton University. Originally published on the American Philosophical Society blog, his post continues the blog series he recently began with a new entry profiling Penn Press’s Digital Operations Manager Lily Simmons and her role in managing Penn Press and APS Press metadata.

In my last post, I talked about APS Press’s effort to catalog and digitize our entire backlist, with the help of our partners at University of Pennsylvania Press and De Gruyter. There, I focused mainly on my own work thumbing through old paper documents and exploring the Library Hall attic. For me, this digitization project has been a surprisingly analog experience.

Today, I want to shine the spotlight on Lily Simmons, the Digital Operations Manager at Penn Press, who has been overseeing the digital side of this operation. Lily manages the metadata for the Penn Press and APS Press catalogs. Each book we produce passes through her capable hands at some point in its journey. If that book is fortunate enough to find a readership, it will do so because of Lily.

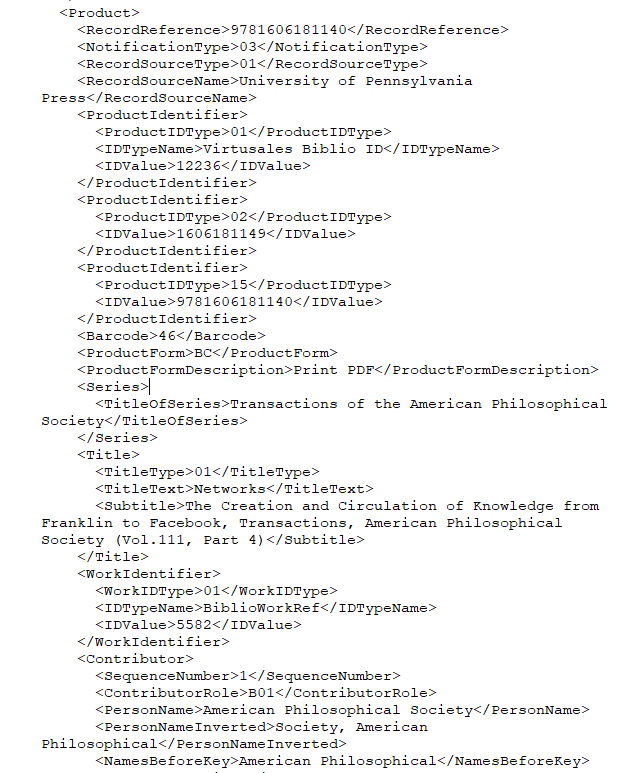

I came to Lily with a question she’s probably tired of answering by now: “What exactly is this thing called metadata?” She explains it like this: Metadata is the set of essential information about a book that makes it “discoverable” in the digital marketplace. It includes everything from the front-end information familiar to anyone who has ever written a bibliography (author, title, publisher, date of publication) to back-end data like sales rights and production specs. Metadata for books is written in a coding standard called ONIX, the current lingua franca of the book trade, spoken by publishers, retailers, libraries, and search engines. ONIX files are transmitted between all these entities to communicate complex information quickly and get books more easily into the hands of consumers.

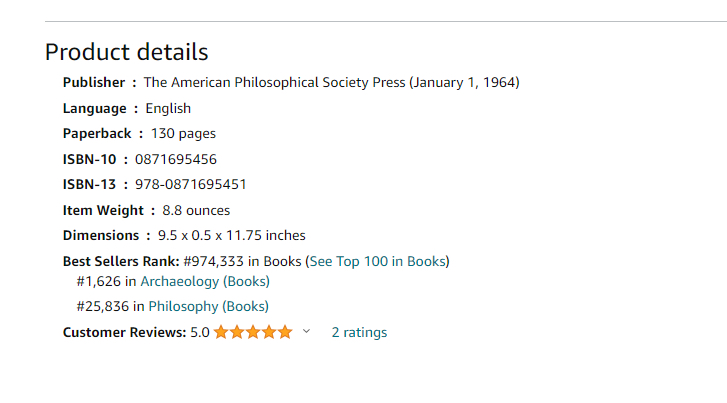

Perhaps the two most important fields of metadata in any given book’s ONIX file are its ISBN, a unique 13-digit identifier applied to all commercial books, and its BISAC codes. BISAC codes classify books according to sales categories, and they can get surprisingly specific. A work of Social Science will be categorized not only under its sub-discipline (Anthropology, Gender Studies, Statistics, and so on), but also according to topics covered (Folklore & Mythology, Poverty & Homelessness, Immigration, among hundreds of others). True Crime, one of the more ubiquitous genres of the past decade, organizes its categories by the offenses involved, from “Abductions” to “Heists” to “Hoaxes.”

BISAC codes are absolutely crucial for discoverability, because they provide the key information used by the search engines that drive Amazon and university libraries alike. If you type “Late Medieval astrolabes” into your search bar, you can thank BISAC codes and the folks who input them for providing you easy access to the APS Press’s own Mechanical Universe: The Astrarium of Giovanni de’Dondi, via HIS037010 (History of Medieval Europe), HIS020000, (History of Italy), and TEC056000 (History of Technology).

Lily maintains the metadata for our backlist and front list, ensuring its integrity and organization. “Without those two things, you’re going to have some trouble selling books.” This maintenance is absolutely crucial in the modern market. An accurate ONIX doesn’t just make like easier for publishers, distributors, and libraries; it connects readers with books. “If consumers can’t find a book, they can’t buy it. They can’t read it. It’s really that simple.” Lily spent months building the ONIX files for over 700 in-print titles, double-checking each input and optimizing them for peak discoverability. “We’re already moving product on the Penn Press website. It’s amazing.”

Lily calls this data-maintenance work “digital forensics,” and it’s one of her favorite parts of the job. “I started at Penn Press five years ago as an Editorial Assistant. I wanted to be an acquisitions editor for Philosophy. But then we had a lot of staff turnover, and suddenly there was nobody in the office who really knew their way around the back-end of a database. So I taught myself. I like solving problems, figuring out how to get from point A to point B in a creative way, breaking down complex issues into discrete chunks. I find this kind of work really gratifying.”

And thank God she does. It’s standard for a publisher to make up to 70% of its revenue from backlist sales. Even without a splashy debut, scholarly books can sell steadily for years or decades. But in order to reach that goal, a publisher’s books need to be easily discoverable for buyers and immediately available for delivery or download. Metadata is the key to this process, and it becomes even more important every year in the Age of Amazon.